The World as a Line

2012, Aswan, Abu simbel, Edfu, Kom Ombo, Philae

EGYPTAFRICAARCHAEOLOGY

"But concerning Egypt I will now speak at length, because nowhere are there so many marvellous things, nor in the whole world beside are there to be seen so many things of unspeakable greatness; therefore I shall say the more concerning Egypt. As the Egyptians have a climate peculiar to themselves, and their river is different in nature from all other rivers, so have they made all their customs and laws of a kind contrary to those of all other men..."

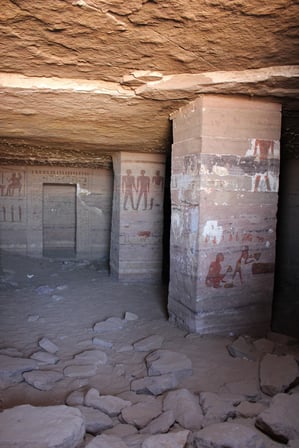

That was Herodotus, sometimes called the father of history. He was a Greek writing in the fifth century BC, an ancient himself from our point of view, and even he needed to take a deep breath when he got to talking about Egypt. He set the tone for generations of geographers after him with that second sentence, noting the intimate relationship between the country and its great river. Indeed it's often said that Egypt is the Nile. I'll join in that chorus here; I could see it with my own two eyes in Aswan, a small town on its upper reaches. I took a train there direct from Cairo, and right away I felt it couldn't have been more different from the capital; lazy, quiet, idyllic save for the odd mosquito. One of the first things I did was walk up to some small tombs cut into a hillside overlooking the town. When I reached the spot I was surprised to find it unmarked and unprotected. Although relatively unimportant, belonging to some minor ancient aristocrats, it was the real thing, and I had it all to myself. For a few charmed minutes I could pretend to be Howard Carter, peering through a collapsed wall into the murk, and then stepping into a tomb. It was dim and silent, the floor had become littered with rocks, sand and a few pieces of rubbish. On the walls though, and on columns supporting the low ceiling, I could clearly see the painted silhouettes of ancient people and their earnest etchings in hieroglyphs. Outside, the view was one of the best I saw in Egypt; Aswan's urban lego-brick colours wrapped in green ribbons, and those cut into strips by the blue stream of the Nile, and all of this hugged from both sides by an endless yellow desert. To ancient Egyptian common sense the world must have seemed neither like a globe nor a disc, but a line. I watched as several dhows floated down along it, paper boat-like.

Aswan on the Nile, Desert hills outside Aswan

Aswan

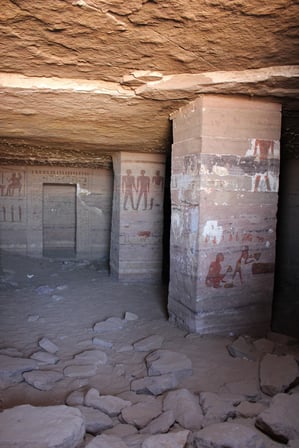

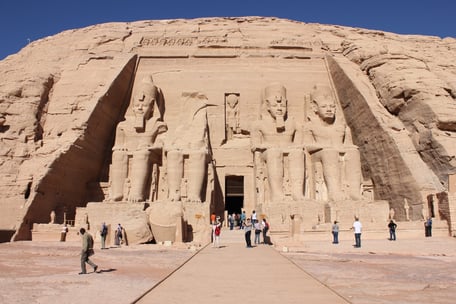

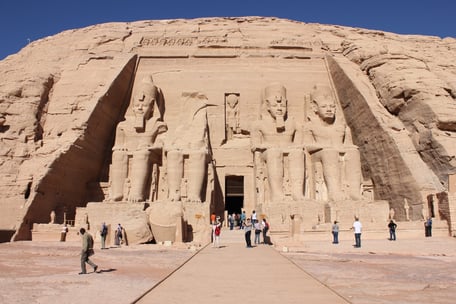

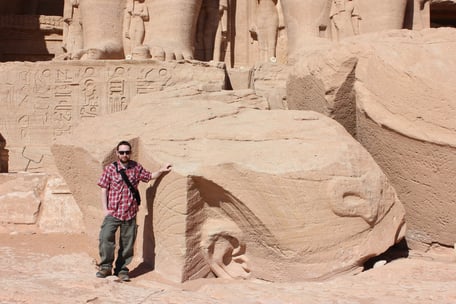

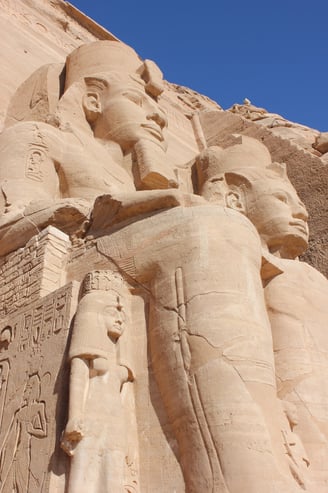

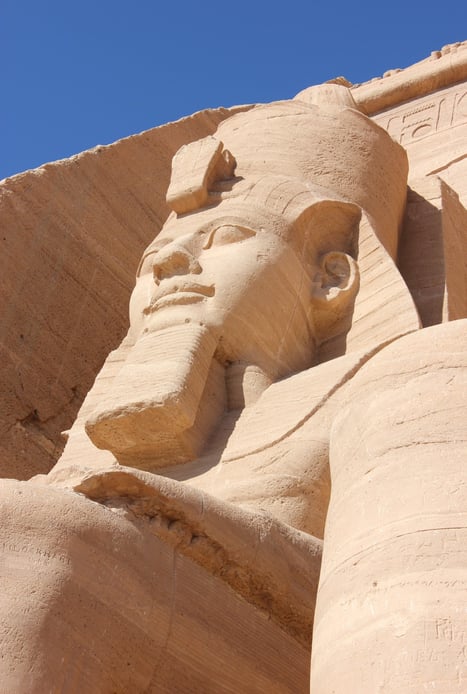

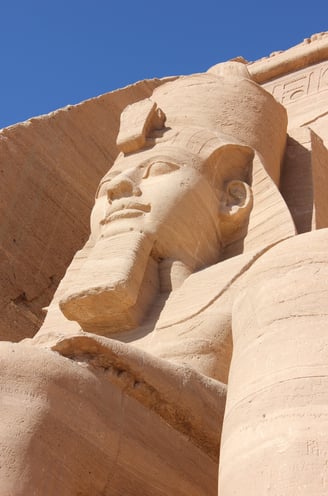

The temples were originally cut out of a cliff beside the Nile, the idea being to awe anyone navigating this stretch of the river and leave no doubt as to who was in charge in Nubia. Incredibly, the entire complex was painstakingly moved by UNESCO in the late sixties in order to avoid it being drowned by Lake Nasser, the new body of water created by the Aswan High Dam. In spite of the move and more than three thousand years under the hard sun, this most famous of Ramesses' building projects has lost little of its power to humble the visitor. It bears stressing the scale of it. One of the statues' heads lies on the ground, placed where it had lain relative to the temple before the move. From its brow, which is pressed into the sand, to the top of the head, it dwarfed me. Inside the temple, the point is hammered home by wall-spanning reliefs of the great pharaoh single-handedly smashing his Nubian and Syrian enemies. In a cute contrast he is also shown hugging and holding hands with his wife, who he was apparently very fond of. In these expressions of love, as well as in the signs everywhere of a gigantic ego and perhaps a fear of the ultimate annihilation of death, it's possible to see through the spectacle and remember that Ramesses and his successors were ultimately only human beings. Not gods, as they liked to imagine, and as you could almost believe, even today.

Abu Simbel

This was close to the end of that line for the old pharaohs, where Egypt becomes Nubia and the Middle East gives way to the African interior. Seeking to cement his power here on the frontier, Ramesses II chose the second cataract of the Nile, in the middle of Nubia, as the spot to build two massive rock-cut temples. Today the site is known by the name of a nearby village, Abu Simbel, about 300 kilometres south of Aswan. Tourists travel with an armed convoy due to the low, but non-zero risk of attack by Islamist militants; Egypt's Wild West has always been its South. Ramesses dedicated the larger of the two temples to himself and rubber stamped the gesture with four colossal statues in his own image. They're still sitting there all regal and serene, enthroned on either side of the entrance. This is one of Egypt's iconic sights, not far behind Giza's pyramids and the sphinx for fame. A short distance away, a smaller temple dedicated to Ramesses' wife Nefertari would be stunning enough by itself if not for standing in the shadow of something several orders more dramatic.

Among those suitably impressed were the last dynasty to continue the Egyptian civilisation at least partly in its original form, the Ptolemaic Kingdom. Beginning with Ptolemy I Soter, one of Alexander the Great's most talented companions, and ending about three centuries later with Cleopatra, this Greek lineage were enthusiastic in their adoption of the native religion and its notions of divine kingship. To been seen as pharaohs however, they would need to build like pharaohs, and downriver from Aswan you can visit two of their best contributions to that venerable old Egyptian tradition. Travelling about fifty kilometres to the north you reach the Temple of Kom Ombo. Though badly damaged over the centuries by floods and earthquakes, the temple is interesting for its atypical symmetrical design and its association with the crocodile-headed god, Sobek. Hundreds of crocodile mummies were discovered on the site, and a few of them can be seen in the nearby Crocodile Museum.

Temple of Kom Ombo, Temple of Edfu

Ceiling, wall detail at Kom Ombo

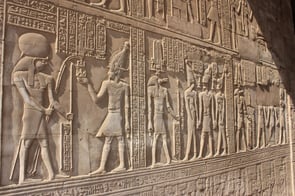

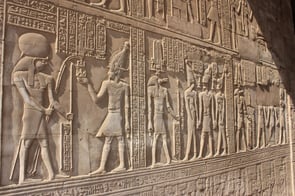

About another seventy kilometres northwards you come upon the Temple of Horus at Edfu. This is a well preserved monumental shrine which can be explored in relative peace, the tourist traffic being mainly limited to a few people stopping off on river cruises. Dedicated to the falcon-headed god Horus, among the many interesting wall reliefs here are depictions of his battles with the god of trickery and chaos, Set.

Temples of Kom Ombo and Edfu

Temple of Philae

Returning to Aswan and continuing just a few kilometres more to the south, you meet the first cataract of the Nile. Here sleeps the drowned isle of Philae, whose famous temple now stands safe and dry on neighbouring Agilkia island, again thanks to the efforts of UNESCO. My visit here was a special experience, completely free from touts and barely interrupted by other visitors. Maybe it was because of the moat around the site, or maybe Abu Simbel is enough for most tourists. Maybe I simply got there early in the day. In any case there were no tour groups, no railings, no "don't touch" signs; once I got off the boat I was free to ramble around the island as if I'd discovered it myself. Philae is a real testament to the ancient Egyptian culture's charisma and capacity to capture and assimilate; the Ptolemaic rulers are depicted here as fully Egyptian pharaohs, and it was Isis and Osiris that had pride of place rather than any Greek deity. It could not go on forever, however. Perhaps exactly because of the gravity of the old religion, some of the wall reliefs here were ultimately defaced by zealots of a new faith; the Christians. For a time the church flourished in Egypt, and it was in this country that monasticism was born. That era too came to an end however, with the Muslim invasion of Egypt in the seventh century. Today the Coptic Christian Orthodox Church still accounts for around a tenth of Egypt's population, and in Aswan a white cathedral occupies a prominent place in the cityscape.

Before those religious upheavals were even a glint in a prophet's eye, Philae had endured as a centre of the native Egyptian religion for centuries; in fact it's believed that the very last Egyptian hieroglyph was inscribed here in the fourth century AD. There were other things written after it; like at Abu Simbel, I spotted a lot of old antiquarian graffiti from the earliest Western tourists. "Markus Pinkerton 1865", for example, thought he'd leave his mark, and it put me wondering how old and how grand something needs to be before it belongs in a place. You might well judge Mr Pinkerton harshly for his presumption, but I couldn't help but feel a little sympathy as well. Just another wee human trying to attach himself to something solid that might not be washed away, down the line.

Collonade, partially defaced relief at Philae

Docks at Philae, View of the Nile at Aswan

The Gist: Aswan

ARRIVED: I travelled to Aswan by train direct from Cairo.

SLEPT: I stayed in a cheap hostel in Aswan, found through Lonely Planet: Middle East.

DID: I found Aswan itself extremely idyllic and peaceful, a place well worth taking your time in between visiting the archaeological sites. I visited Philae and Abu Simbel by bus organised in person in Aswan. For Kom Ombo and Edfu, I arranged a driver through my accomodation.

LEFT: I travelled by bus (booked in person) north to Luxor.