The Motherland Calls

2018, Mamayev Kurgan, Volgograd, Battle of Stalingrad

RUSSIAEUROPE

I think this is the year I've truly become a thirty-something, that is to say, someone who sometimes catches himself forgetting the second digit. It was the ninth of June, and in between reassuring myself that I was about to turn thirty-two and not something else, it dawned on me that I hadn't planned anything for it. My birthday happens to share the twelfth of June with Russia Day, the national holiday which commemorates the country's re-branding after the fall of the Soviet Union. In Russia, a bridge holiday is often given to connect national holidays to a weekend, and so I would have both the Monday and the Tuesday (Russia/John Day) off work. Despite not preparing anything beyond a single can of Guinness in the fridge, I did have the presence of mind to book the following Wednesday, Thursday and Friday off as well. So I had a full free week ahead of me. But how to spend it?

Marking 32

It was a long trip, but not uncomfortable. I shared my cabin with three other passengers, all Russian and with only a few words of English between them. I muddled along with my rough foundation in their language and we kept a surprisingly healthy banter going. I had assumed - incorrectly - that the train would have a restaurant car. Sure enough though my cabin mates showed the same habitual kindness to strangers that by now I've encountered many times in this country, and shared their food - and cognac! - with me.

In Russia it isn't difficult to spend a lot of time travelling. In fact, it's not even necessary to mention the famous Trans-Siberian route in order to talk about truly vast expanses here. At thirty-two hours, the journey to Volgograd struck me as apt enough for a birthday present to myself. The city takes its name from the river Volga, long ago a border between old Russia and the Tatar steppe. In more recent history here was Stalingrad, the hero city where the awful tide of World War II (to Russians, the Great Patriotic War) was finally turned. I made my decision and booked the train tickets, and packed my can of Guinness along with some light luggage. I would depart alone the following night, a Sunday, and arrive in Volgograd early on Tuesday morning, my birthday.

Taken just after I'd dropped my bags in Volgograd

Mamayev Kurgan

After two nights on the railroad, we rolled into Volgograd's impressive, fortress-like railway station at around five in the morning. Shortly before arrival my companions beckoned me to the window. The giant statue “The Motherland Calls” had come into view. This colossal figure stands on the hill known as Mamayev Kurgan. At first I thought "Mamayev" might be connected to the name of the statue, but in fact it goes back to Mamai, a notorious general of the Golden Horde in an era when the Russians were still confined to lands further west. There's no question who the hill belongs to now though. The statue is a gigantic personification of Mother Russia in concrete and steel, measuring 85 metres from her feet to the tip of her raised sword. For comparison, this dwarfs the Statue of Liberty's 46 metres (excluding the plinth it stands on).

I wasted little time after dropping my luggage at my Airbnb studio apartment, and set off on foot back along the railway track towards the hill, approaching the statue from the south side. As I would discover later, the architects no doubt intended a different route. Coming from the river, you climb through several tiered stages of monumental ensembles calculated to build a sense of awe as you ascend towards the statue. I missed this on my first visit to the site, though the great statue more than took care of first impressions by herself. Even from some distance away I had to stop several times to take it in. Not only is she truly huge, but her dramatic pose adds to the impression. Her left hand is thrown back, calling her sons and daughters to action; her right arm raises a hefty sword high against the enemy. To look at it you almost expect to see an army approaching on either horizon, but instead there's a sharp juxtaposition with the fairly mundane profile of the modern city.

I suspect even a visitor with no knowledge of the war would sense it. Something titanic occurred in this place, in an era now fully past but still visceral; a story fit for high fiction. As I climbed the hill and approached the statue, I had a number in my head: 1,000,000. A million men died here. Though it's difficult to believe, that is rounding down the true death toll of the Battle of Stalingrad from something considerably higher. As a strategically crucial piece of high ground, Mamayev Kurgan saw some of the fiercest fighting, with the ground here changing hands multiple times during the five-month struggle from August 1942 to February 1943. Walking up the hill with a warm sun and a light breeze on my face, I thought about my generation's blind luck, born into a friendly country and a gentle moment in history.

Memory lane

From the statue I descended towards the riverbank, passing that series of further monuments along the way. The path down the slope took me first past a series of plaques to the Soviet war dead where Russians were leaving fresh red flowers, and beyond that there was a statue of a grieving mother holding the shrouded body of a son. At this point I heard a choir, a looped recording coming from a great circular hall. The path led me into it, and spiralled inside round a great stone hand holding a torch with an eternal flame. The curved walls of the hall are coloured gold, and reflect the light of the flame. A plaque in front of the flame is guarded by two expressionless sentries.

A little further down the hill, a wall bears etchings of the soldiers, an artist's imagining of what the human beings who died here might have been like. I was struck by the effort to give personality to every figure; courage, humour, even swagger. Not to say that it would be better, but I noted that fear and suffering were not depicted here. Continuing down, there was a serene pool of water flanked by statues; brothers in arms wrestling snakes and struggling through dire circumstances. After that there was another set of steps with a wall on either side seemingly made out of debris, brickwork destroyed by bombs. Out of this material the shapes of tanks and planes and steely faces are carved. In case the drama might be lost on anyone, another looped recording booms out a cinematic narration over the whine of diving aircraft and the thuds of distant explosions, reaching a peak of emotion in the spine-tingling hurrah of men charging to the front.

Finally a tree-lined boulevard ushered me down to the river, Mother Russia still looming high over my shoulder. The last statue I met - normally the first to greet visitors walking in the opposite direction - is a macho fusion of muscle and machine, someone's ideal Soviet man with a rippling torso and clutching a machine gun, seemingly ready to squash any foe. I can imagine this piece in particular coming off a bit bombastic or over the top to some visitors, and to some extent that's probably true of the whole complex (and the Soviet art style in general). The prevailing feeling for me though was deep poignancy. This place is effectively a religious shrine, built by an atheistic regime. The emotion expressed towards the fallen soldiers, most of them just boys, is palpable. The Motherland Calls struck me as somehow both a child-like expression of hero-worship and a survivor's sombre salute, cemented together in grief and gratitude.

Mamayev Kurgan casts a long shadow over Volgograd, and after visiting the iconic site you might reasonably ask what else the city has to offer. The answer is that you haven't gotten away from the Great Patriotic War just yet, whether you like it or not. The Panorama Museum: Battle of Stalingrad hosts a meticulous collection of artefacts from the time and is really the second obligatory stop for any visitor to the city. History buffs will be delighted with the rich collection of information on display, though when I visited you needed to get an audio guide for English. For someone more casually interested there's still a lot to connect you to the history in a more concrete way, whereas the monuments up on the hill can only allude to it - grand and all as they are. Here you can find a Soviet commander's great coat, still cut by the bullets fired from a German fighter plane. In another room, a rifle once aimed and fired by the famous sniper Vasily Zaytsev. Standouts like these are surrounded by all the panoply of war; weapons from pistols to artillery platforms, grimly purpose-built bomb shells, battle flags, propaganda posters, medals, the twisted metal innards of wrecked tanks and planes. Even without reading the information displays you get a strong sense of the industrial nature of the war - the sheer weight of inert material taken out of the earth, warped into a lethal shape and then pressed into human hands to throw at human bodies.

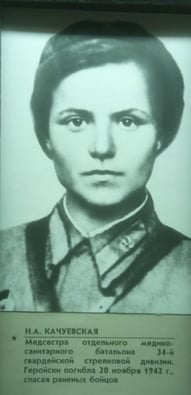

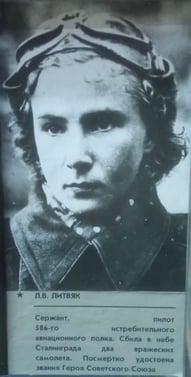

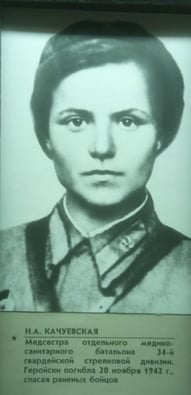

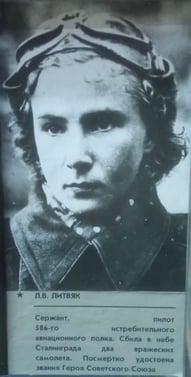

Besides this visceral kind of impression offered by the battlefield artefacts, I also found one collection of photo portraits very affecting. An interesting thing can happen with any picture of a human face. If you spend more than a few seconds looking at it, you can observe yourself doing what you no doubt do all the time subconsciously when you meet someone face to face - you start to form a working hypothesis of their character. Your brain runs scenarios and guesses how the person might react. You imagine speaking with them. Look a little longer, and you may find yourself imagining their whole life story. You might like to consider the faces below yourself for a moment before reading my translation of the information given about them.

These are just four faces that happened to catch my attention out of many, many others. I think I picked them out mainly because they reminded me of people I know. In my previous post I mentioned that well over a million people died at Stalingrad, but that's only saying a number. The tragedy comes into focus when your mind grazes a human story, and from there you can begin to trace the silhouette of all those gallant young people who stood up when the whole world seemed to be falling down. The presence of women among the ranks of the men was very noticeable here, speaking volumes not only about their own mettle but also the totality of the war on the Eastern front. As a Russian friend of mine once put it to me, "it was about whether we would continue to exist or not".

Moving from the intimate to a more detached and yet more immersive perspective of the battle, the museum hosts a room-spanning mock-up of the wartime cityscape onto which a light show projects the movements of the two opposing armies. At first there is the city in peace time, then dark clouds roll in ahead of the first air raids. After a gratuitous series of bombings from the sky, the tug of war begins between the land armies. The Soviets are spot-lit in bold red and gold, the Nazis in a sickly grey-green, almost suggesting physical infection.

What really sets this museum apart though comes at the top floor, at the end of a winding stair case. The whole building is capped by a great circular room. Inside, the curved walls present a 360-degree panoramic painting, imagined from the perspective of the top of Mamayev Kurgan at the height of the battle. As you scan the scene you witness a legend, frozen in one chaotic moment. Planes diving and strafing, now crashing, tanks charging with turrets turning, bodies heaving along trenches, eye contact between enemies, dire warnings shouted and triggers pulled. Not accidentally, a dark cloud hangs over the invading Germans and the sun breaks through where the Red Army has taken the advantage. As you leave the museum you pass a parade of accolades from all over the world. Lavish gifts from the USSR's fraternal communist states like Vietnam and China stand alongside equally gracious gestures from the West, among them a specially forged ceremonial longsword sent by King George VI and delivered by Winston Churchill himself. You can also see a note in Churchill's own handwriting from the time of his visit, expressing hope for a new beginning.

(From left to right)

N. A. Kachuyevskaya: A battlefield nurse. "Died heroically on the 20th of November 1942, while attempting to save wounded soldiers".

L.V. Litvyak: A fighter pilot. "Shot down two enemy aircraft in the skies over Stalingrad. Posthumously awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union" (presumably she was killed in action).

A. V. Alyelyukhin: Captain Commander of a fighter plane division. "For courage shown at the Battle of Stalingrad, awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union" (his fate isn't mentioned).

G. B. Provanov: Lieutenant Colonel Commander of a tank brigade. Posthumously awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union (presumably he was killed in action).

From allegory to artefact

Volgograd, versus Stalingrad

Although the legacy of Stalingrad still looms large over today's Volgograd, the modern city does show some signs of building a story and a character of its own. My visit came just a few days before England versus Tunisia, the first of four World Cup games to be hosted at the new Volgograd Arena. I didn't have tickets, but I stopped by to see some of the preparations anyway. That was my last day in the city, and I rented a bike to cycle along the riverside promenade. This long stretch of smooth concrete and trimmed grass contrasts with the scruffy waste ground on the opposite shore, visually marking the current extent of Moscow's generosity. I joined the path at the tall bridge that spans the river and then pedalled north towards the stadium. It being early in the morning, the path was only sparsely peopled with the odd fisherman or roller-skater and I could speed along as fast as my legs would let me. As much as I enjoyed myself, I realised quick enough that stopping to rest and take in the view wasn't really an option with the local breed of mosquito out in force. I powered on uphill to the Volgograd Arena. Finished just in time for the championship, it's a modern and polished looking structure that seems to beg further development in its vicinity.

The minor heart attack of the day came a little later. Cycling past a pair of strolling policemen around the back of the stadium, I felt my front wheel go over a what I thought was a plastic bag. I shrugged and coasted on. Just a little further up I came to a dead end - luckily, as it turned out. Coming back around I spotted my passport where that plastic bag should have been, maybe twenty metres ahead of the approaching policemen. It'd slipped out of the small satchel I had slung over my shoulder, left unzipped while beating a hasty retreat from a cloud of biting insects at my last rest stop. On my journey home I compared and contrasted the different fates that might have followed, first if I'd never realised I'd dropped it, and second if those friendly neighbourhood officers had reached it first. Foreigners travelling in Russia are supposed to register with the police at each stop in their itinerary, usually through their hotel. I was staying at an Airbnb and hadn't bothered, but luck was with me this time.

On my way back to base I chanced upon Hiroshima street, doing a double take as I recognised the name rendered in Cyrillic. The infamous Japanese city was twinned with Volgograd after the war, in recognition of the shared experience of unprecedented devastation. Some housing blocks along the street feature interesting, frantically coloured murals on their faces, including one with many eyes looking earnestly out at... something. I suppose you could interpret that one a few different ways.

My last port of call was the return to the railway station. The building had made an impression on me the morning I arrived and it looked even more impressive lit up in gold at night. I think you can see the old Soviet social ethic embodied in Russia's rail terminals. Much like the country's famous metro stations, these buildings seem to have been imagined as secular cathedrals, grand architectural celebrations of the new socialist society rather than merely practical nodes in the transport network. Volgograd's is an especially good example, with its stout clock tower and dramatic statuary. The station suffered a terrorist attack in December 2013, but shows no sign of it today. In the square before the entrance I saw a strange fountain lit up in purple - children dancing in a circle around a crocodile, a scene from a fairy tale. This is a replica of the famous Barmaley fountain which became a symbol of Stalingrad after appearing in wartime photographs, a little bit of innocence oddly juxtaposed against the shattered city.

As I waited to board my train, I first heard and then saw some of the lead detachments of football fans arriving in Volgograd, and I wondered how they would spend their time before and after the football. I suppose some would go and pay their respects to the past, while others might just have been there to celebrate the present. Fair play to them both.

The Gist: Volgograd

ARRIVED: I took a sleeper train from Saint Petersburg, booked online with Russian Railways.

SLEPT: I found a nice apartment on Airbnb for 1500 RUB per night, which I think was a bargain in the run-up to the World Cup.

DID: Mamayev Kurgan is the great visual draw in this city, with the Panorama Museum: Battle of Stalingrad providing the information to support the spectacle. I enjoyed exploring the modern city by bicycle, in particular the new stadium is worth checking out.

LEFT: I returned to Saint Petersburg by train.