Ozymandias

2012, Luxor, Karnak, Deir el-Bahari, Colossi of Memnon, Dendera, Valley of the Kings

EGYPTAFRICAARCHAEOLOGY

I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert... near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal these words appear:

"My name is Ozymandias, king of kings;

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!"

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away...

Percy Shelley began writing this poem in 1817, probably inspired by the British Museum's bagging of a bust of the pharaoh Ramesses II, known to the ancient Greeks as Ozymandias. The "traveller from an antique land" is the historian Diodoros of Sicily, who long ago reported an inscription under a giant statue in Egypt: "King of Kings Ozymandias am I. If any want to know how great I am and where I lie, let him outdo me in my work." If there had been a microphone, he would have dropped it. Shelley put his finger on the eeriness of the pharaoh's boast, arguably never answered by anyone who came after him. It was time that softened his cough in the end, though not even time has yet managed to fully quieten the civilisation of ancient Egypt.

Luxor and Karnak

Its voice echoes loudest around the site of Thebes, "City of the Sceptre", the capital during the Middle Kingdom and the New Kingdom. The city standing there now is called Luxor, and it was my next stop on my way back north from Aswan. Considering the weight of attractions packed into the area, I found it surprisingly cheap and easy to get around. There was a little more hassle from touts than in the south, but still much less so than at Giza. I did have one memorable run in with a would-be guide. He started pestering me by the bank of the river, persisted while I retreated onto a ferry and kept up the sales pitch for the whole crossing. Once we'd gotten moored on the other side he stopped abruptly, without apology or goodbye, and broke off as if he'd remembered he needed to be somewhere else.

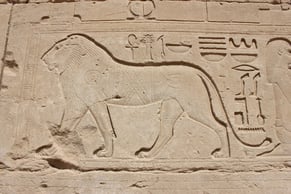

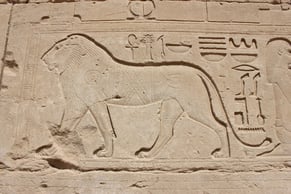

On the east bank of the river I visited the temple complexes of Luxor and Karnak. Egypt may be known primarily for its pyramids, but here is where you find the full flower of its creativity in stone. At the entrance to these temples and their inner courtyards, you pass by the towering bulk of the pylon gateways. With their aura of permanence and impregnability, they have apparently inspired the design of today's banks. There and again later inside you meet obelisks, which by their angle and by the inscriptions they carry seem to point urgently and insistently at something up above and beyond us. Every later empire worth its salt has felt the need to cart one off, or at least knock off an imitation to decorate its own capital. Sure enough the entrance to the Luxor temple looks slightly lopsided, with one of its original flanking obelisks now in Paris. Nonetheless undaunted, the remaining smooth, inscrutable statues watch over the passageways, many with the face of our Ozymandias. And especially in Karnak's Great Hypostyle Hall, row after row of bulbous pillars overawe the lilliputian tourists and dampen the din of the crowds.

Leading southwards from Karnak, a processional avenue lined with ram-headed sphinxes once led all the way to the Luxor temple, and enough of it remains today to fire your imagination. In its absence though you wouldn't be hard done by, strolling down along the Nile. The two temple complexes can be visited comfortably on the same day, and I'd recommend visiting the larger, Karnak, in the morning or afternoon to have plenty of time to explore. Luxor temple makes for a good evening, to wind down and finish with a view of its proud ramparts lit up at night. These are mesmerising places even without reading a page of the history, which of course they are both heavily burdened with. Luxor, "the southern sanctuary" was dedicated to the renewal of kingship - think Canterbury, but an order of magnitude more grand and more ancient. Alexander the Great claimed to have been crowned here, in an effort to legitimise himself as the new pharaoh once he had snatched Egypt from the Persians. Karnak, which the ancient Egyptians called "The Most Selected of Places" was adorned with monuments starting no later than three and a half thousand years ago during the eighteenth dynasty, and continuing all the way into the Ptolemaic kingdom which followed Alexander's conquest. It was only formally closed in 323 AD, along with all other pagan temples then remaining in the Roman Empire.

Luxor

Karnak

Luxor, Karnak

Deir el-Bahari and surrounds

On the west bank of the river there's a glut of other sites to visit, all very impressive in their own right even after the spectacle of Karnak and Luxor. Of these, the stand-out must be the temple of Hatshepsut. This is something unique in Egypt in more ways than one; Hatshepsut was a woman, and as pharaoh she commissioned an original temple for herself with rows of colonnades bisected by a monumental entrance ramp, the whole edifice cradled by the steep cliffs of the valley of Deir el-Bahari. Statues of the queen complete with pharaonic false beard still decorate some of the temple's columns. Much of the site was defaced however by her nephew and successor Thutmose III, along with most visible historical mentions of her name. It remains unclear what exactly motivated this damnatio memoriae, a deliberate attempt to erase her from history, but scholars conjecture that her gender was seen to have created religious problems or cast doubt on the legitimacy of the dynasty, this in spite of her prolific reign of over two decades.

Turning back towards the river, another short walk delivers you to an otherworldly scene. Buffeted by the stream of traffic heading into town, but calmed by the verdant fields of a valley below sandy hills, I watched a white donkey swishing his tail. He'd been given a break from pulling the cart behind him. Looming there in the background sat two giants, the Colossi of Memnon. Again the mythical character lends his name; this time the real author was Amenhotep III, and originally his twin likenesses guarded the entrance to a gigantic temple, bigger even than Karnak. Here though time had allies in its assault; earthquakes and floods have levelled all but the two statues, and left them even them badly eroded. A short visit was enough to survey the physical extent of the site, but the air around it was heady. I remember having the feeling as I set off home along the motorway that I had passed onto some new level, that now I had really seen something of what the world is.

Just a short walk to the south of Deir el-Bahari you'll come upon the Ramesseum, the "House of Millions of Years". A huge statue here is missing its upper torso and head, which now sit in the British Museum. Called the "Younger Memnon" after an Ethiopian warrior from Greek mythology, this is in fact Ramesses II, the Ozymandias who put Shelley's pen to paper. Near the lonely legs, the head of a twin statue still squats in the sand, giving an eerie echo to the vision of the poem.

A fifteen minute walk south from the Ramesseum brings you to the often overlooked but well preserved temple of Ramesses III at Medinet Habu. The form of the temple is similar to what would have originally stood at the more eroded Ramesseum, and holds fascinating wall reliefs including depictions of the invasion of Egypt by the mysterious Sea Peoples during the late Bronze Age collapse. Many of the tour groups seem to ignore this site. When I visited I had it almost completely to myself, and could enjoy a relaxing ramble around the reliefs comfortably shaded by the high temple walls.

Colossi of Memnon

Medinet Habu

Temple of Hatshepsut

Temple of Hathor at Dendera

On a fresh morning I returned to the road and took a detour north, away from Luxor to where the Nile twists sharply westward. Nestled into the kink of the river sits the Dendera temple complex, one of the best preserved in all of Egypt. This place competes with everything else for the sheer impact it has had on my memory. There's a whole assemblage of different buildings to explore at the site, but the highlight is the Temple of Hathor. A meticulous cleaning effort has revealed the original brilliant paints of the ceiling and pillars, giving a better impression than probably anywhere else of what an ancient Egyptian temple really looked like. Forget that innocuous sandstone yellow, the builders here had a full palette, from warm reds to cool azures. I must have spent an hour with my neck craned up and my jaw slack, just trying to take in every detail of the starry skies, choreographed snakes and apes, and gesticulating gods and goddesses. Hathor was the primeval mother goddess. At the entrance, rows of columns culminate with her head, and as a whole this "House of Hathor" seems to preach the procession of all life from her. One unique feature of the temple is the so called "Dendera light", an image which fringe theorists have jumped on as evidence of ancient Egyptian electrical technology. A bit less dramatically, Egyptologists see a lotus flower rather than a glass bulb and a snake rather than a filament coil. No rewriting of history just yet then, but it does highlight the richness and expressive power of ancient Egyptian art.

Valley of the Kings

Returning to Luxor, funnily enough the greatest marvel of all the many here is also the most discrete. A little to the north of Deir el-Bahari lies the famous Valley of the Kings, home to the underground tombs of the New Kingdom pharaohs. Where the other monuments I've described were built to loom over generation after generation, these were meant for an audience of zero; the corpse of the king. As a modern tourist of course I'd be politely disrespecting that wish, but at least a little decorum is enforced inside the tombs for practical reasons. Photography is not permitted, and entry can only be made as part of a carefully shepherded tour group. For this reason I have no photos of my own to share (plenty of course can be found elsewhere on the internet). On the surface there's only the desert and the walls of the valley, the entrances to what look like giant rabbit burrows are simple rectangles. But once you step inside, the journey to the afterlife begins. Gently hemmed in by wooden banisters, we glided softly down under a luxurious blue and gold ceiling, past columns on either side all subtly lit as if by candles, whispering at us through their hieroglyphs and pronouncing revered truths through their images of gods and men. The main memory I can convey is that it was surprise, after surprise, after surprise, so much so that it felt stupid to say anything, and I was quiet.

The Gist: Luxor

ARRIVED: I travelled by bus from Aswan, booked in person.

SLEPT: I stayed in a budget local guesthouse in Luxor, found through Lonely Planet: Middle East.

DID: Within Luxor city itself I visited the Luxor and Karnak temples. On the west bank of the river, the Valley of the Kings, the temple of Hatshepsut, Medinet Habu, the Ramasseum and the Colossi of Memnon are all clustered within walking distance of one another. Their distance from the city centre is a half an hour taxi ride or a one to two hour walk on foot (including a ferry crossing). Dendera meanwhile is the only site I've mentioned here which requires organised transport, at a 1 hour 15 minute drive from the city.

LEFT: I travelled by bus to Suez via Hurghada, booked in person.