Hanging in the Air

2018, Meteora, Mount Olympus, Thessaly

EUROPEGREECERELIGION

Greece on a map looks like the complicated root system of a big plant, called Europe. Like the boot of Italy, its shape is easy to recognise, drawn with a steady but playful hand, it reaches down into the teeming waters of the Mediterranean. Its capital Athens sits on the neck of the bulb, surrounded by water, and looking out to the many little islands which define the country for most visitors. In fact, most of Greece happens further north, away from the sea, where the land widens from a peninsula into a continent. I said good luck to my Dad after a week travelling together around Corinth and the capital, and met up with my old friend Stratos, a Greek I know from when I lived in Budapest. We’d given ourselves a week to get to Thessaloniki, capital of that different Greece up north.

The hours ticked away on the bus, notches up the spine of the country. There was plenty to talk about, we hadn't seen each other in a bit over a year. I was still reeling from a break up, while my friend was going to great lengths to delay one of his own. But we talked, like we usually do, about what was going on in the world at that time, what had been going on several thousand years previously, and other such over-serious stuff. We did not talk about our girlfriends - yet. I noticed a girl getting onto the bus who I thought looked just like one of those Greek statues, but I didn't bring her up either.

Up, up and away

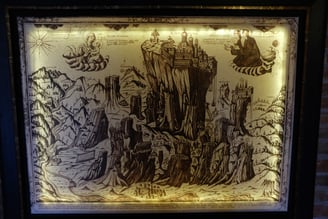

Of course it doesn't take a week to get to Thessaloniki from Athens unless you're making a few stops. We rolled in to Kalabaka on a Monday evening, just as the sun was getting orange, and we already understood it had been a very good idea to come to this place. Kalabaka is a small, neat town nestled below the great rock scaffolds that have made this place famous. The rocky bed of the earth is thrown up into tall shapes, leaning and jibbering, like a party of drunken giants. I thought of childhood dinosaur colouring books and the Flintstones. It is a primeval landscape. In fact there is a cave not far from the town, at a place called Theopetra, which bears signs of Neanderthals, then after them the first hunting-gathering representatives of our own brand of human, and later again the first European farmers. Many people stopped here on their way into the continent, but the most visible mark was left in the ninth century by the monks who founded monasteries, stupendously, on the tops of the rock towers. They gave the place its name, "Meteora", which means "hanging in the air". Think "meteor".

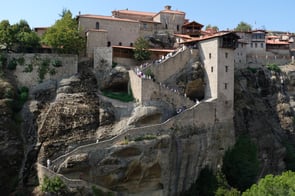

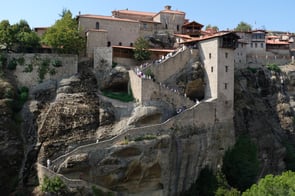

The sheer faced pillars on which the monasteries are perched look as intimidating as they do majestic, and they were chosen exactly for the physical as well as spiritual seclusion that they afforded. Just looking at them I'd expected a challenge in getting up, something along the lines of my experience visiting a similar place in Ethiopia. For most of Meteora's history it's true that access was only by way of a rope ladder or windlass, but nowadays it couldn't be easier, up a few steps or over a bridge from the road. I strongly recommend walking between the monasteries to take in the full whack of the landscape, which is at least as important here as the hand of man. It's not a difficult walk at all, especially if you take the bus from Kalabaka up to a starting point on the high road to the far side of the pillars. Of the original twenty-four monasteries, six remain active. You could visit every monastery in a single day, but take note that during week days at least one of them may be closed. The summer timetable for 2018 (April 1st to October 31st) was as follows:

Monastery opening hours

Great Meteoron: 09:00 - 16:00 Tuesday

Varlaam: 09:00 - 16:00 Friday

Rousanou: 09:00 - 17:00 Wednesday

St. Stephen: 09:00 - 13:30, 15:30 - 17:30 Monday

Holy Trinity: 09:00 - 17:00 Thursday

St. Nicholas: 09:00 - 16:00 Friday

We had a Monday and a Tuesday to explore Meteora, so on the first day we visited the two largest monasteries, Great Meteoron and Varlaam, and on the second we took a bus to St. Stephen and then walked downhill to the town of Kastraki, visiting most of the other monasteries along the way. With a Greek friend in tow you might not be charged anything, as we discovered, but as of 2018 the entrance fee for most visitors was €3 at each monastery. This is a little funny in that the size varies a lot between the six. Nonetheless, they each offer a unique vantage point over the valley and together help to build a picture in your mind of the world in which the monks have lived for over a thousand years. Although only a handful remain today, Meteora is still considered a holy place for Orthodox Christians. I was interested to note the profile of the visitors, with many Greeks and quite a few Russians, their co-religionists. Photography is not permitted inside the monasteries, and so you should put away your camera as you enter. Don't worry, it will see plenty of action outside.

Monasteries in the sky

The most spectacular view in Meteora is probably from the outcrops above Roussanou monastery, where we stopped to wait for the sunset on the Tuesday evening. We rested our feet in a round hollow at the edge of the platform, scooped out by the same great potter's hands that sculpted the valley; the wind, the rain, and time. We were looking west, Roussanou off to our right, Varlaam and Great Meteoron further on behind it, and a huddle of giants across the valley off to our left. My friend told me that my failed relationship was not what I had built it up to be, that it was time to move on, and although I didn't accept it at the time, he was right. We stayed a long time on the outcrop and arrived at St. Nicholas too late to see it, the smallest of the bunch. I was a little disappointed, but not very.

A Slovenian girl we met along the way remarked that she had been expecting more of an immersion in nature, and I’d agree there was a contrast between the well-tended grounds of the monasteries, the modern roads linking them to the town on the one hand, and the wildness of the geology on the other. It is not quite that place of hermetic seclusion any more, that the giant landforms would still seem to imply. They nevertheless towered above us undiminished as we walked back into town, and we were waxing lyrical, high on the whole experience by the time we got down to Kastraki and remembered our stomachs.

And that’s where I stopped writing. With that last sentence there, I mean, not in Kastraki. It was 2020, the Covid time, and I suppose I’d gotten tired of living in my head. That and I was about to make a move to Spain, a place where many new memories would be made, and old ones apparently overwritten. I pick up the trail now a full four years later, with a little help from my travel buddy Stratos. He remembers better than I do a dinner with two Portuguese girls, one of them the statue I’d seen get on the bus before. He found her boring rather than statuesque, and her friend more to the other extreme. She was giving out about the Greeks not giving her back her one cent change at the till, for which she got, inexplicably, some amount of sympathy from me. Meanwhile a bouzouki player and singer worked away there in the background and somewhere south of my friend’s standards. The only part of his account that my own memory can corroborate is the end of the night, where he was punished for the non-event of the evening with a long telephone argument with his soon-to-be ex. From the sublime to the ridiculous, sure tis but a step, so they say.

Stratos had booked an Airbnb in the town, but when we got there the host was confused. He’d ignored the names on the reservation, having assumed there was a couple coming, based on Stratos’ soon-to-be-ex profile picture. There was only one bedroom, well, there was another one but it was locked. We were also banned from using the washing machine, and there was no Wi-Fi, a problem back then. I took the couch in the sitting room. As for the washing machine, “you said fuck that shit, and you were right too”. Stratos also remembers me being in some distress, needing emotional support, because I was going for a job in the department of foreign affairs, a junior diplomat role. If I remember right, I might actually have needed to go through one of their IQ test style filters during the trip itself. I did get through that in the end, and the next part, a nerve shredding group task that I flew back to Dublin from Saint Petersburg especially for, only to fail to tick all the boxes at interview. I wouldn't have remembered any of that now, I don't think, if he hadn't mentioned it.

There be gods

The next day, we took our time strolling back to the train station. Stratos remembers catching the dark eye of a passer-by, who we’d later meet again on the train. We ate lunch in a sun splashed plaza, under the welcome shade of trees, and I ordered a meat platter for myself. I offended Stratos by eating with my elbow on the table, and as I absent-mindedly chewed on bones, staring at my phone, I trampled local and international food etiquette alike. Ever the stoic, he bore it with equanimity. Soon we were on our train to Litochoro, the small town which would be our base for visiting Mount Olympus, the famous abode of the gods of old Greece.

Our train cabin-mates were two solo travellers around our age, one of them that one who Stratos had spotted before, a beautiful Lebanese-Australian girl with short dark hair. The other was a bearded, bespectacled, wise-browed guy from Israel. One of them made a crack about everything being late, and then told Stratos to take it easy, having misread offence in his muted reaction. I meanwhile was much less worried about stepping on anyone’s feet, and straight away got to probing the politics of Israel and Palestine. I wouldn’t be so forward these days, but back then I liked to do that whenever I met Israeli travellers. I’d noticed that they always seemed to have one thing in common, no matter the personality or other demographic; to me they always showed the signs of having thought a lot about the big questions, about the past and the future. How could they not, I suppose, after compulsory military service in a country where war was a real prospect. Stratos remembers one nugget we got out of him; he noted that Israel had not had a civil war. He remarked that maybe this meant the country was somehow “half-baked”.

The Australian girl talked about how the Greek and Lebanese communities in Australia are “one thing”, how she had been raised sharing in the feast days and celebrations of both alike. Probably again at my prodding, she also talked about indigenous Australians. She remembered a moment in her cohort’s shared coming of age, when the aboriginal children became aware of history, and no longer related to the white kids in the same way. At some point the attendant stuck his head in and cut us off. “LIT-O-CHO-RO” – he helpfully sounded out the syllables for us, drawing giggles from Stratos.

Once in town, we could already see Olympus. I was surprised to discover its shape; not the snow-capped cone template of my mind’s eye, but somehow shorter and stouter, forested most of the way up, and then crowned with a wide, pale wall of rock that dips in an oblique V shape, like a gigantic shrug, or a smirk. I could sort of see how you might imagine a city there, and a home for the famously temperamental, slightly terrifying family of gods headed by Zeus.

The next day we stopped on the way to Olympus to get cream and nutella bougatsa, a pastry native to northern Greece and the perfect mid-morning snack. Fuelled up, we started our climb. Let me clarify before I go any further; we’d scaled back our plans a bit. The most popular route to climb begins at Prionia (1,100 meters elevation) and ascends to the Mytikas peak (2,918 meters), the highest point in Greece, and this was what I’d originally imagined us doing. Olympus is regarded as a moderately challenging climb, requiring good fitness, but not technical mountaineering skills. However, since we were short on time, had not trained and had not brought proper gear for rain or cold, we decided not to push things. Instead we opted for a hike through the national park which surrounds the mountain, going at least some of the way up its shoulders. Neither of us can remember the exact trail we followed, but I know we hiked for at least a couple of hours and passed the Sacred Cave of Saint Dionysios, where a little chapel sits snugly in a recess in the rock. A little further on, we also saw the Old Holy Monastery of Saint Dionysios. We swam too, in a limb numbing stream coming down from the frozen heights, and I did my bit of dare-devilling, venturing out onto an outcrop over a sheer drop. I remember we talked less than at Meteora, and mostly enjoyed the silence, quietly fighting to be the first to the top. The signpost for a taverna stood at the end of the trail, and we symbolically drew our little unspoken race on the spot, clapping hands on it as one. We ate heartily just before last orders, there at the forested feet of the true trail. That rocky road to the summit would have to wait for another era in our lives. We met some luck as we started back down, and caught a lift to town with an old German hippy couple. We made chit chat on the drive, and they made a point of noting that Greek people were very nice. “Which I always take as an insult”, remembers Stratos. “I think it hides stuff that they don’t want to say”.

The Gist: Thessaly

ARRIVED: We took a bus from Athens to Kalabaka to visit Meteora, and then continued by train to Litochoro to visit Mount Olympus

SLEPT: We used Airbnb in both Kalabaka and Litochoro.

DID: At Meteora, we visited 5 out of the 6 monasteries, over two days, mostly on foot but also taking advantage of the local bus to cover the uphill journey out from town. At Litochoro, we did a short hike along a forest train leading to the Monastery of Saint Dionysios.

LEFT: We continued by train to Vergina - well, we would have, only we missed it and had to take a taxi instead. A story for another post.