Footsteps in Fatherland

2018, Athens, Attica, Acropolis, National Archaeological Museum

EUROPEGREECEARCHAEOLOGYMUSEUMS

The streets seemed to be empty. I came to one open shop doorway where an old woman was sweeping with the radio on. I'd forgotten how to say good morning, so I just said "Internet?" with a rising intonation. She gave me a short, neutral answer in Greek and then went back to her sweeping. After a while I rounded a corner and spotted a café. It was shuttered, but I sat myself down for a rest on a concrete bollard and took out my phone to look for a signal. Success! A message burst through from Nireas: "Im therebin 1 mjninute". I punched in a stern "Ok, we're waiting" and started marching back up the hill. My heart sank when I got back to the doorstep; no Nireas, no auld fella. I tried not to think about worst case scenarios, and a few minutes later my host appeared at the door full of apologies and ushered me upstairs. The padre was already busy inspecting our lodgings. Before I could do anything else, I needed a nap. When I woke up, it was to warm Mediterranean sunlight and vibrations from my phone. That was my friend Stratos, asking for first impressions of his nation's capital. A few months before this he'd had an encounter with some socially inept stranger in a bar. This character had been to Greece, and as soon as he'd copped he had a Greek in front of him, he proceeded to hold forth on how the country had failed him as a traveller and a person of culture. There wasn't enough left standing, and whatever did catch his eye had been sub par versus say, Italy or Egypt. Being far from a chauvinist himself, my friend had no ready-made riposte. Later this annoyed him greatly, and though he worked some of it out of himself through writing, he'd gotten a little anxious that I might be disappointed with Athens as well.

He needn't have worried himself; we hadn't even started exploring yet and our curiosity had already been stoked. I told Stratos how Dad and I had agreed that Athens felt a bit like a South American city. It was Europe but with a layer of something else. What that something else is, I'm not sure. Maybe it's the East; for an age before the Roman Empire and after it under the Ottomans, Greece was bound to Asia in one way or another. Or it might just be the heavy weight of the country's own unique history. Modern Athens feels like a tectonic plate, floating on a deep, still stirring ocean of time. Before you've even visited any historic site, the old language comes to your eyes and ears. Apparently we get 6% of our vocabulary from Greek, and we use most of it for the hefty stuff; science, philosophy, religion. As such, for an English speaker paying even a little attention there's an odd feeling of familiarity. Here something as mundane as an exit sign reads έξοδος, "exodus", and the word for "thank you" is ευχαριστώ (efcharistó), from which we get the Christian eucharist. I joked with Stratos about how the names of the city districts, like Neo Psychiko or Exarcheia itself, sounded more like alien planets, mental disorders, tropical plants or books of the Bible.

Foreign but familiar

Early last September, two Irishmen were waiting on a sleepy street in Exarcheia, Athens, at half past eight in the morning. They were alone except for a homeless man opposite them, who was asleep on a raised bed beneath a mosquito net and a clean white sheet. His bed was set between two pillars on the street, and above his head he had put up a map of his country and a pair of icons. He had one foot stuck out from under the bed clothes. The elder of the two foreigners was standing up straight with his arms folded, while the younger, drawing the majority of the mosquitos, had begun to pace back and forth. They were waiting for an Airbnb host by the name of Nireas, and Nireas was half an hour late. The two men had the same nose and ears. It was myself and my father, at the beginning of our long anticipated if lackadaisically booked tour of mainland Greece. We were tired after the overnight flight from Dublin but our spirits had been high up until around that point. I glared at my watch, wondering where I might have landed myself and the auld fella. The journey in from the airport had been smooth, by train to the connection with the metro at Syntagma station, then on to Omonia. "More like ammonia", we joked after getting above ground. Dad's guidebook had forewarned him that the neighbourhood had a certain reputation, and the first sights and smells seemed to confirm it. As we marched uphill to our accommodation, the graffiti on the walls got thicker, and there was a sense of going off track and into the woods. And so of course Nireas was late; Nireas probably wasn't coming. With a heavy heart I acknowledged that I had no local SIM card and I couldn't call the man. We agreed Dad would keep watch for our host while I would go and try to find some public Wi-Fi. I was glad not to be standing around. In fact I was too tired to be all that bothered about the situation, and I started to look more closely at the graffiti as I strolled back a little way downhill. I saw that it wasn't graffiti at all, really it was right and proper to call it street art. I stopped to admire the murals several times along the way, forgetting and then remembering my mission.

A great way to start a visit to Athens is to climb one of the city's hills. The most famous of these is the Acropolis, site of the Parthenon, but before going there it's worth seeing things from a different angle. We visited Lykavittos first. It's an easy walk up a paved pathway, or alternatively you can ascend by funicular railway. There are two summits, one hosting a church and the other an open air theatre. The view encompasses the sprawl of the modern concrete all the way out to the sea. Islands of the ancient city protrude here and there, cradled in the protective green of trees. They look almost like the whitened bones of dinosaurs, dead but still bearing the mark of old agency and intention.

High points

Acropolis simply means "high city", and there are many other acropolises in Greece. But The Acropolis is the one that belongs to Athens. There can't be many places in the world where so many of history's heavy hitters once walked. There were the playwrights that left us the oldest tragedies; Aeschylus who told us how Prometheus stole fire from the gods, Euripides who dramatised the voyage of the Argonauts and the ill fated romance of Jason and Medea, and Sophocles who recounted the doom of Oedipus. On the lighter side there was Aristophanes and the beginning of comedy and satire. In medicine there was Hippocrates, from whom we get the Hippocratic Oath, still taken by medical graduates today. Herodotus, called the Father of History, also must once have climbed the hill. And probably most famous of all are the great philosophers; Socrates and his student Plato who created the foundation of ethics, and Aristotle who continued their tradition and tutored the young Alexander the Great. The banners of armies too numerous to count have been carried up the slope and hung from the ramparts. Starting with the Persians of Xerxes I who destroyed the first, "Archaic" Acropolis in 480 BC, this hill was later claimed by Rome's legionnaires, centuries on by the knights of a diverted Fourth Crusade, later again by Venetian marines sent by the Doge, Catalan mercenaries from Aragon, the Muslim armies of the Ottoman Sultan, and even by soldiers of the Nazi Third Reich. Undaunted by all this history, today the calm blue and white flag of modern Greece flutters over the citadel. On the way up to meet it you pass by a whole complex of storied monuments. Most impressive along the south slope are the Theatre of Dionysus and the Odeion of Herodes Atticus, the latter of which was being prepared for hosting a musical performance the night after we visited. Rounding the corner north of the Odeion you meet the Propylaia, the remaining parts of the monumental ramp, staircase and gateway leading up to the plateau of the hill. Of note here is the little Temple of Athena Nike, above you on your right as you climb. Once you reach the top and pass under the archway, the Parthenon comes into view and you feel you have arrived definitively in Greece. Easily one of the most famous buildings in the world, it's a mark of its massive influence that the architecture feels familiar in form, if not in scale. The Parthenon was built by the Athenians under Pericles to be bigger and better than the older monuments which the Persians had destroyed. Originally dedicated to the goddess Athena, during its long history it would also serve as a Byzantine church and later an Ottoman mosque. The original building remained essentially intact and respected during these later times, only receiving a new roof and the addition of a tower when it became a church, replaced in turn by a minaret when it became a mosque. In the seventeenth century a Venetian bombardment detonated an ammunition dump inside the building, destroying its mid-section. The Ottomans promptly built a new, smaller mosque on the spot, though without disturbing the remaining front and rear of the old Parthenon. Independent Greece has since then made efforts to remove most of the post-classical buildings from the site and partially restore it to its ancient appearance. With a little imagination you can picture the building with it's original brilliant red and blue paint, and housing the now lost Athena Parthenos, a gigantic cult statue of the goddess in gold and ivory.

With your back to the Propylaia, the Parthenon stands ahead to your right, while straight ahead the Sacred Way once trodden by ancient Athenian religious processions continues on to the Belvedere. This was once the site of a Crusader tower, demolished along with the other medieval and Ottoman structures on the Acropolis. Today this is the spot where the Greek flag flies, atop some surviving battlements and a great viewing point facing the north-east of the city. If you come here early or late enough you might catch the raising or lowering of the flag by the jauntily dressed Greek Presidential Guard, the Evzones. From here Dad and I could look back out at Mount Lykavittos, the first hill we had climbed at the start of the trip. With your back now to the Belvedere you can return back up the Sacred Way and get a closer look at the Erectheion, a smaller temple famous for the Caryatids; stout columns in the slender shapes of women. The sun was setting as we began to leave the site, ushered firmly out by the site's attendants. We watched the sun descend a little in the sky from the steps of the Propylaia, and then continued straight down and west to Pnyx, last but not least of the Athenian hills on our itinerary. This rocky outcrop was once an open air town hall for democratic assemblies. It remains a great spot to watch the sun go down over the city and gaze back at the Acropolis before finishing the day.

The entry price for the Acropolis and its slopes was €20 when we visited in September 2018, but for €30 you could buy a combined ticket giving access to several other open air sites for a period of five days. If you visit at least two of these in addition to the Acropolis, then the price is worth it. The following are some highlights from the sites included.

The Olympeion, or Temple of Olympian Zeus: This was once the largest temple in Greece, and though only a part of it remains standing the scale of the building is still impressive. This could serve as a nice appetiser on your way to the Acropolis, which looms over the site.

The Ancient Agora: Once the busy marketplace of the ancient city, this tree shaded space combines history with the feel of a relaxing walk in the park. It also contains one of the best preserved temples in Greece, the Hephaisteion, or Temple of Hephaestus, which survived intact for centuries as a Greek Orthodox church. The Agora also has its own museum, which is itself a reconstruction of an ancient building, the Stoa of Atallos.

The Roman Agora: We arrived here late and couldn't enter the site, but we were able to peer in through the railings. The site is relatively small and contains a few impressive standing columns and arches. It also hosts the unique Tower of the Winds, or Aerides, a kind of ancient meteorological station.

Aristotle's Lyceum: There is not much left physically standing here, and the appeal lies more in putting your feet where the great philosopher once walked and taught. Unfortunately, we didn't have time to visit it ourselves.

View of the Acropolis from Lykavittos

Later in our trip we climbed Filopappou hill by night. This is the legendary home of the Muses, and fittingly enough the tempo of our climb was set by a drum circle hidden somewhere among the trees. The hill is surmounted dramatically by the one remaining sector of the tomb of Philopappos. This man was a prince from what is now Syria, and was held in such high regard by the Athenians of the second century that he was given this place as his grave, commanding a height over the city forever. It bears pointing out the changed political realities, with so many modern Syrians being met on the shore as aliens, if not criminals. Besides this unique monument, the hill affords a fantastic view of the Acropolis, closer up than from Lykavittos. When we climbed there were only one or two other people at the summit, and soon we had the place to ourselves. We sat for a long time taking in the Parthenon, all lit up in gold by night. If the bits of old Athens are a skeleton, then that’s the skull, and it crowns the city just as it has done for two and a half thousand years. Before we left the summit, Dad spotted the hotel where he would have stayed. There had been a business trip planned for him in Athens once, but it fell just before his father, my grandfather, passed away. He became silent, and I think he might have said some words in his mind. He was not unhappy though.

View of the Acropolis from Filopappou

Top left to bottom right: Olympeion seen from Acropolis, vice versa, ancient forum, Hephaisteion

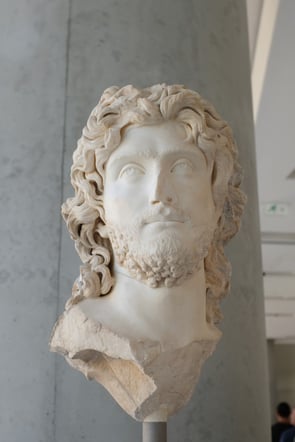

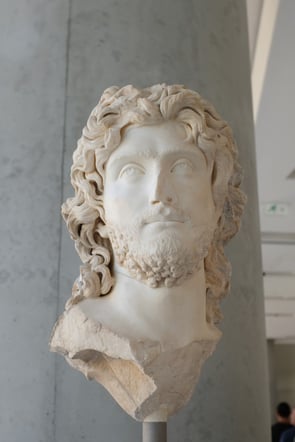

If you still have some appetite left for history, or you just want to get out of the sun, Athens has some of the best museums in the world. At the top of the list is the National Archaeological Museum, where you can begin to get a sense of Greece not as just one persona, but rather a group of cultures evolving through time and interacting through space. The museum collection includes a wealth of ceramics decorated with warriors and sea creatures in black and orange, finely engraved coins, weapons and other artefacts. What left the biggest impression on me though were the sculptures. In metal, most impressive are the bronze statues recovered from a shipwreck off Cape Artemision on the island of Euboea. The Jockey of Artemision is a life size recreation of a boy riding a race horse, and the simply titled Artemision Bronze is a larger than life statue of the god Zeus preparing to launch a thunder bolt (or possibly Poseidon brandishing his trident). Like with the architecture of the Parthenon, I think there's something almost disconcerting in the sophistication of these ancient works of art, which seemed just as good to me as anything being made today. In stone, the funerary stelae are as poignant for their emotional content as they are impressive for their workmanship. These are elaborate grave stones depicting the deceased and the bereaved. In many the surviving family members are bent over in grief, while the dead reach out to console them. You can also catch a glimpse of Athena's own ghost in Varvakeion Athena, a Roman era copy of Athena Parthenos. Though only a small fraction the size of the original giant statue, it's considered to be faithful in form and helps to fire the imagination. Travelling further back in time, there are the enigmatic sculptures from the Cyclades islands in the Aegean sea. Carved out of pale marble, their flat faces and stylised, lyre-like figures immediately suggest their influence on modern art. They also made me think of Easter Island's giant moai, with their sloped profiles and inscrutable facial expressions. Nowadays when we see a statue, we see a statue. Something makes me think that for ancient people the experience was something different; to sculpt the form was to call an entity to life. It's interesting to ponder whether the stylised forms of early Greece and many other cultures before and after them might have been a deliberate choice, more befitting a deity or an ancestor than the down to earth realism which the Greeks eventually pioneered and which we now treat as standard in art.

Archaeoligical museums

As darkness fell over Athens we descended through narrow streets back towards the metro line, now and then casting a glance back up at the Acropolis. Never far away, the audacious murals of today's young Greeks winked and whistled at us from their concrete canvasses. They seem to proclaim that whatever tyranny might sit upon Athens, nothing can squash her overflowing creativity for very long. Our morning in Exarcheia frankly had not inspired confidence in the night, but when we got back we found the neighbourhood buzzing with hipsters dining outside and artists milling around plying their wares; the air was thick with conversation and the smells of good food. We settled down for a meal, and I asked my father to tell me a story he'd never told me before.

The museum holds several unique or almost unique artefacts, each in a class of its own. One example is the gold funerary Mask of Agamemnon from Mycenae, a relic from the archaic Greece of the Trojan War or even earlier. There are also some distinctive frescoes belonging to the Minoan civilisation of Crete, connected to the legend of the Minotaur. Most mysterious of all is the Antikythera mechanism. This was a primitive clockwork computer, designed to predict astronomical positions and track important events in the ancient calendar, such as the cycle of the Olympic games. This is a real example of a single archaeological discovery rewriting history and forcing us to reconsider the capabilities of ancient people. Dad and I managed to find it on our way out just before closing time.

Also well worth a visit, the Acropolis Museum was built to protect and showcase the huge amount of material found either standing or buried on the hill. After the Persians destroyed the first Acropolis, the Athenians reverently interred the ruined stonework on the spot. This "Persian rubble" includes many fine votive statues once commissioned by Athenian citizens in order to win the favour of the city's patron, Athena herself. The most common types are the idealised youths, the male kouros and female kore. Coming from the early "archaic" period, to me their style is reminiscent of Egyptian art. Like with most Greek architecture and sculpture, they would originally have been painted in bright colours, and the museum includes video displays to help bring this aspect to light. Going up in scale, you can see what remains of the pediment of the gigantomachy, huge statues from the archaic temple depicting Athena and her allies destroying an army of giants. Finally, you can see what remains of the frieze, metopes and pediments of the Parthenon. Places have already been prepared for the "Elgin" marbles, which the museum hopes to one day welcome back from London.

Top left to bottom right: Artemision Bronze, Jockey of Artemision, Cycladic figurines, Varvakeion Athena, Funerary stele, Mast of Agamemnon, ancient piggy bank (?), amphora with octopus

The Gist: Athens

ARRIVED: We flew to Athens from Dublin with Aegean Airlines, and the journey was as comfortable as you could hope for with an overnight flight. From the airport we took a train to Syntagma station, from where we connected to the city metro.

SLEPT: We stayed with two different Airbnb hosts, both in Exarcheia district where there was a great balance of price and proximity to sightseeing. Although at first we thought the neighbourhood seemed a little rough around the edges, we weren't long in being proven wrong, and I wouldn't hesitate to recommend the area. Do note however that here, as elsewhere, Athens is not a flat city.

DID: We climbed several hills to get different views of the city; Lykavittos, Filopappou and Pnyx. The most famous attraction in Athens is the Acropolis, which is a much bigger site than just the Parthenon, and worth a visit of at least several hours. We visited two museums, the National Archaeological Museum and the Acropolis Museum. We also visited a couple more archaeolgical sites, the Olympeion and the ancient agora. We really enjoyed the bohemian atmosphere, outdoor dining and street art in Exarcheia. Not described in this post, I also visited the ruins at Cape Sounion from Athens.

LEFT: After our first stop in Athens I travelled with Dad around southern Greece. We then returned to Athens, from where Dad flew home and I continued northwards with my friend Stratos. We took a bus to Kalabaka from Loission Terminal B, close to Kato Patissia metro station. This is the same station Dad and I came to for our bus to Delphi.