A Dinner With Wolves

2015, Stepantsminda, Mount Kazbek

EUROPEGEORGIAPOLITICSRELIGIONHUNGARY

I manage a surreptitious scratch of the red blotches on my thigh. Szervusz is a polite form of address in Hungarian; good day sir, how do you do sir. The hair on his head and face are thick and black, and there's a suggestion of biceps through his red windcheater. Softening that, there’s a gentle bulge in the belly. He has good hiking boots and the brand of his clothes is one of those you have to pay for. He halves his snickers bar and gives me the part with the wrapper still on, and we chat there on a shoulder of the trail. It turns out he listens to Irish music and drinks Irish whiskey. As a matter of fact he’s got a bottle of Jameson back in the hostel, and two of Hungarian pálinka. There’s going to be a party this evening, and we'd be happy if you joined us, John. Isn't this a nice little coincidence. I was enjoying the quiet, but you know, I just might. We continue.

"Szervusz", says the friendly fascist. I stop there, jerk my neck back a little, into the slope of the hill behind me and away from this surprise. I give him a broad smile with the teeth and the eyes and ask him, "Magyar?". At this stage I don't know his politics, you see, just that he's Hungarian.

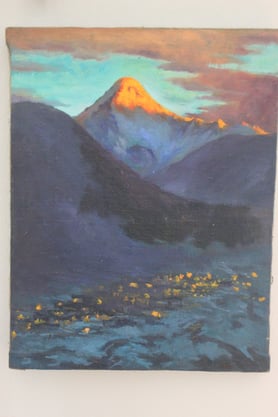

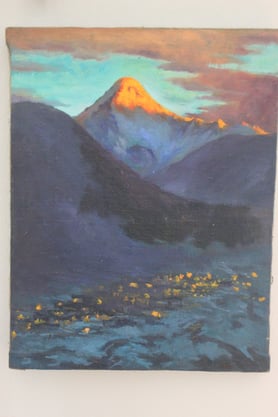

It's grand mild weather for hill walking and we're both on our way down from the Gergeti Trinity Church, a little hermitage on a grand perch above the town of Stepantsminda. In Soviet times, they built a cable car shortcut to the site, maybe in a subconscious challenge to its air of aloof moral authority. Today though, only the ruined terminals remain, tottering, all brittle concrete and broken beer bottles. Now again as once before, when you look up there from the valley, you’re told a tale of the scale of things, instantly and without words. There sits the little house of holy men above the world of ordinary folk, but then higher and further, immanent yet utterly beyond, stands Mount Kazbek, a frozen eruption of the Earth in gold and pitch. There could be no better metaphor for the Man Upstairs. Giant and all as it stands, it can play hide and seek, now veiled in mists, now coming startlingly into view. When you see it, your mind touches masses and measures not of our human world, and then it slips away again, evaporates into air.

I had three travelling companions, university classmates from Slovakia, but they have had their fill of Georgia's highlands after our visit to Mestia, and are now relaxing by the Black Sea at Batumi. I've stayed up here for more of this mountain euphoria, and for the rest that's in it for an anxious mind. I found plenty of both in the hermitage, and more besides climbing the trail higher still. At last I could see a wall of ice, a glacier at the foundation of the clouds. That was far enough for me. I suspect there are bugs waiting in my bed, but this has been worth it. Which is saying something.

His girlfriend catches up with us and I get chatting with her. He’s taking his time, minding his knees on steep sections, and before long he has fallen out of easy earshot behind us. She knows Russian, that’s interesting. I have met a Hungarian lady that could speak it before, but she was in her sixties. It was more common for people to know German, and much more common again of course, English. Georgia is something new for me though in that my native language is, not to say useless, but less useful than the Slavic common denominators sieved out by my friends from Slovakia. This country has a language all of its own of course, a whole strange mountaineering family of languages at that, but still to some extent or other it is under the Russophone sphere, struggle as it might to get away from it. I must try to learn Russian at some stage. That big cold country with the onion domes, the backward letters and the bearded villains, looming now just twelve kilometres to the north.

“Yes, Russia is a good country. We feel very comfortable when we travel there too”.

“Oh, how so?”

“They are proud of their country, and they have a strong leader. They know what is important, what is right and wrong”. I’m paraphrasing, but you get the idea.

I go a bit quiet.

"And do you travel a lot in..." I begin blandly, but she wants to round off her point.

“They don’t have feminism there” she adds, brightly.

Well now, aren’t I grateful to be walking alongside her, and not sitting facing her. My left eyebrow has gone up, caught in a fishhook. Just a minute now and I’ll get the right response to you.

"Yes, we like to travel in eastern countries” she returns to my question, graciously. “It's cheaper, and, well we just prefer it. What did you do in Hungary?"

Thank God. "Oh I got my braces there, it's cheaper, ha. And then last year I went to university there."

Her eyes narrow just a twitch at that. "Oh really, what university?"

"CEU. You know, the Central European University".

She nods, but darkly. "Oh."

A silence, made manageable by the walking, the hands tucked tightly under backpack straps.

Then, “Our hostel is just up this path, you’ll join us won’t you?”

She doesn’t wait for an answer.

And so, the path just sort of carries me along with them, she ahead pulling and he behind pushing. I’m boxed in, like an unlucky runner. I don’t want to call her back or him forward to tell them no thanks, and before I know it, I’m being seated at a long table, and there’s a lot of food on it. A Georgian lady is adding to the already substantial spread, and casting little questioning glances at me which seem to ask whether I’m a paying guest. My fascist friend, who I will call Farkas, simultaneously raises and dismisses the issue in one exhalation, aimed vaguely in the direction of our hostess. Of course, there is plenty of food to go around, feel at home.

Don’t mind if I do, Farkas. There’s meat and veg to beat the band, all soaked in oily sauces, heaps of fresh bread for the dipping. Cheese everywhere. Will leave the analysis to my stomach frankly, I’m hungry, and it’s easy to relax the mind when you’re attending to affairs of the gut. I’ll just eat this and then say goodnight. The only thing is, the table blocks my route to the door, I’m seated in the middle, and now he’s pouring the pálinka. Alright, represent the nation and all that, I wouldn’t say no. Farkas sits to my left, in terms of physical location. His girlfriend, who I’ll call Réka, is at the left corner opposite him, near enough for me to continue talking with her. Ringing the table on my right are three to five other members of the fascist hiking club. There’s a balding but solid man in his fifties, with cold eyes, a younger one in his twenties, with greasy black hair and a crooked smile, and a willowy blonde woman who seems only to listen and laugh but not to speak. If there are others, from my perspective they serve only to enhance my sense of being outnumbered. They are all quite civil and acknowledge my presence when directed to do so.

“John lives in Budapest”, announces Réka, and then significantly, “he went to university there”. Brow lines jerk in sudden curiosity, and her eyes dart around to meet them.

“Which university”, inquires the older man. His shoulders are a solid square, and the nails of his right hand come up now to gently scratch the cut of his jaw.

A hazy premonition of danger, but something urges me onward. “CEU” I reply cheerfully, but the words are no sooner out than I feel the ground give out from under me. The party exchange glances; lopsided grins, eyes out the window, looks of indigestion. Farkas is observing me.

“Which department”, the younger one with the greasy hair wants to know. In his eyes, the glint of an arrogant intelligence. They narrow now with anticipation. Really, he is asking on behalf of the group, and they want me to say business or urban planning, something innocuous. Probably even history would do.

“Sociology and anthropology”, I declare. Usually goes down well at a gathering. Not this time.

A weighty silence now, lasting a good two to three seconds. I am alone at the table, and the group will defer to Farkas, their leader, the matter of how to deal with this. These wolves, who have by accident invited a sheep to dinner. A nice little coincidence indeed.

I did my master’s at the Central European University in Budapest from 2013 to 2014. I got a partial waiver of the fees; most successful applicants at that time got at least that if not also a stipend, thanks to the generosity of the founder, George Soros. The billionaire Hungarian-American set up the university in his country of birth after the fall of the iron curtain to foster a progressive political culture and an open society, his bit to boost the movement away from authoritarianism in eastern Europe. It was indeed a movement to recast the region as central Europe.

But for every action, as they say, there’s a reaction. Soros' name is now maligned on both sides of the Atlantic as one of the preferred bogeyman of the Right, a powerful moneyed interest with left-wing symathies, who also happens to be Jewish. As I write, looking back from 2025, CEU is now based in Vienna, with only a shell of the university remaining in Budapest. This fate was sealed in 2017, when Victor Orbán and his ruling Fidesz party introduced legislation known as "lex CEU". Similiar to earlier tactics deployed against foreign NGOs in Russia, the law imposed new requirements on foreign universities in Hungary, specifically designed to put CEU into a state of non-compliance. Although CEU attempted to meet the new requirements by establishing programs in the United States, the Hungarian goverment simply refused to acknowledge them. In 2018 the university announced it would be forced to leave the country. The European Court of Justice ruled in 2020 that Hungary had violated WTO rules as well as the EU's Charter of Fundamental Rights, but the damage was done.

Orbán was ironically once himself the beneficiary of a Soros scholarship, as a young anti-communist liberal studying at Oxford. Notoriously, he would later style his governing philosophy “illiberal”, and steer the country steadily away from the European consensus on a whole range of issues on top of academic freedom, maybe most notably the response to the 2015 migration crisis. But for a time, the wind at his back came from another political party, Jobbik, for whom Orbán was not going far enough. In Hungarian the name means both “better” and “further to the right”.

I’m surprising myself with how well I can put away the drink this evening; no doubt it’s the mountain food. My innards are armoured in fat, thick enough that the palinka can’t even dent it. Now I can feel the whiskey burning through it, but slowly. He pours another.

Farkas’s decision is, in all fairness to him, a magnanimous one. We have invited John to eat and drink with us, and so that’s what we’re going to do. As a CEU humanities alumnus, there can be little doubt that he has been thoroughly brainwashed by the Marxist-Leninist-Feminists known to lord over that department, but here we are. We are deep in it at this point. And it probably doesn’t hurt that I have the pale skin, the reddish beard, the lazy heterosexual get-up, to code me as coming from acceptable stock, however misguided.

“I have heard there is gay marriage in Ireland now. How did that happen?” inquires Farkas. Réka is listening intently. He is referring to the 2015 amendment to the Irish constitution, which allowed marriage to be contracted by two persons without distinction as to their sex. I understand from his question that he thinks this was a disaster, and that we red-blooded and Christian Irish could only have had it forced upon us by some insidious political elite.

With some pleasure, and buoyed by the alcohol, I join battle. It was approved by referendum, and resoundingly so. Farkas and Réka exchange looks of genuine surprise. I have a sense of a reassessment, a weighing up in Farkas’s mind. I begin to understand that I am present at this dinner partly because of his conception of the Irish, a heroic nation of the right hue, harassed by history but standing true. A lot like the valiant old Magyars of his imagination, no doubt.

“And what is your opinion of it”, he pushes.

I must admit that I didn’t vote - but only because I was away in Hungary. Yes I support it. I can see that he doesn’t, I tell him, but I don’t need him to. I do think though, that his own logic should force him to agree that people should be able to make decisions about their own lives. This seems to strike a certain chord with him, and he nods for what seems a long time, holding eye contact as he does so, and I take it as an acknowledgement of a fair point.

Farkas gets up to go and relieve himself, and Réka picks up the baton. If everyone becomes gay, where will children come from? Her tone is a little agitated but confident, and she waits for my response. It’s the first direct assertion from their side of the night, and I’m a little knocked off balance by how silly it is. It’s a hollow slap, it lacks the weight of pre-meditated malice I’ve been steadying myself for. Something a child might say. But they have been listening to me, I think, with complete patience.

Well, where is the evidence of something like that happening, I lay out simply. If it seems like there are more gay people now, it’s because they were always there but it’s only now that we can see them and hear them. Her reply is a rewording of what she’s already said; she’s discombobulated, but not remotely persuaded. She seems happy enough just to leave it there.

When Farkas returns, he wants to move on to migration.

John, you must agree that nations have the right to defend themselves. Maybe Hungary and Ireland will not even exist in twenty or thirty years. I get a bolt of inspiration and take a punt on his Irish rock chops. Do you know Thin Lizzy? He does. Then you know Phil Lynott. Isn’t Ireland the more for having had him, the son of a migrant father and an Irish mother? Farkas offers no counter to this, and again gives me that long, even nod.

I buttress it, and appeal to his conception of history. For two centuries in Ireland we had the penal laws, the legalised subjugation and oppression of the Catholic majority. If you agree that’s wrong for one time and one place, to treat one crowd one way and the rest another based on whatever category they were born into, then isn’t it wrong for all times and all places? He lets this one go too, without retort.

These wolves must have gone soft with their full stomachs. The consensus around the table seems to be that this sheep is a good one, it’s a pity he’s been so misled, but we like something in him. Maybe it’s the fire in my belly, but I’m not afraid of them. On the contrary, I’m on the offensive.

I see the opening to cross-examine, and I ask Farkas where exactly he stands politically, what does he think of Jobbik. He gives a little wince that seems to acknowledge the gravity of the question, and then he begins to nod again. He confirms it quietly, yes, he is a Jobbik man. And not just a voter, he is an elected party member. Yes John, I am your enemy. You are mine.

The bottle is empty, and the group is breaking up, skulking away. Farkas has told me where his allegiances lie, but he has not really told me who he is, not until the end of the night, just before I finally make to leave. He will first give a summary of our conversation, some preamble. You have said many reasonable things, John. I’m glad you came here.

“But you know, the greatest threat to Western civilization in our time is the Jew”.

It rolls off his tongue like a practised formula, as a plain fact. Even after everything this evening, I can’t believe it, and I look for some glint of self-parody in his face, a grin or a wink or some twinkle in the eye. All I get is a freezing stare.

He sees me off at the road outside. It seems like we’re both aware the whiskey will only burn so long, and then the night will get very, very cold. Best I get back to my own lodgings before that happens. He tells me again that he’s glad I came, that he has enjoyed our talk. Honestly, I have enjoyed it too, in the way that I enjoy getting lost in deserts and walking too close to cliff edges. He talks optimistically about hiking together in the morning, but I think he knows it won’t happen, and we do not exchange contact details. He offers me his hand, and because I am leaving a house where I have been given food and drink, because it is a reflex, and because I am drunk, I shake it.

The moon is out, round and white and drawing up a net of stars around it. They tremble and swim in my eyes, but I see the path well. It will not be a hard walk to my bed, where the bugs will find my blood a rich cocktail of proteins, of alcohol and adrenaline. As long as I keep myself back from the slopes, I will wake up in town, in the valley, and make my way back to my friends.

In 2020 Jobbik attempted to rebrand themselves as reasonable conservatives, if you ask me doing a bit of a disservice to that edgy wordplay. They have since sunk into irrelevance, their support scattering to the splinter radical nationalist Mi Hazánk Mozgalom (Our National Homeland) and the new centre-right Tisza party. Any remainder have seemingly gone to ground, politically disengaged for the time being. Orbán's Fidesz party have meanwhile maintained their now fifteen year long stranglehold on Hungarian politics, and increasingly aligned themselves with Russian narratives after the full scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

The Gist: Stepantsminda

ARRIVED: By bus from Tbilisi.

SLEPT: In a local informal B&B which I found on arrival.

DID: In town I visited the beautiful little St. Gabriel the Archangel Church, and the small, interesting Stepantsminda Museum of History adjacent to it, which has some paintings of the locality and some enthnographic displays. The main attraction though is the hike to Gergeti Trinity Church. It's worth continuing up a bit further to get the view of the church from above, and to catch a glimpse of the glacier. Spend at least a couple of days to enjoy the spectacular mountain scenery. Whatever the company!

LEFT: Again by bus back to Tbilisi.